On 9 December the US Senate voted to approve the 'Henry J. Hyde United States-India Peaceful Atomic Energy Cooperation Act of 2006' after a series of revisions since President George Bush and Prime Minister Manhohan Singh signed an initial agreement in July 2005.

Once President Bush has signed the document and it becomes law, four further agreements must be made:

- A specific agreement between India and the International Atomic Energy Agency regarding safeguards of nuclear materials.

- India-specific trade guidelines must be drafted by the Nuclear Suppliers Group, a 45-nation cartel which has restricted nuclear trade to NPT signatories since 1992.

- The USA must conclude a '123' agreement with India on nuclear cooperation. Section 123 of the US Atomic Energy Act of 1954 requires an agreement for cooperation as a prerequisite for nuclear deals between the USA and any other nation.

- The Indian parliament must agree to the text.

Following this paperwork, American companies will be able to do business in India, which is keen to have access to the USA's advanced technology and skills. The US-India agreement could also form the basis for similar agreements between India and other countries, such as Australia which is seeking new markets for its uranium.

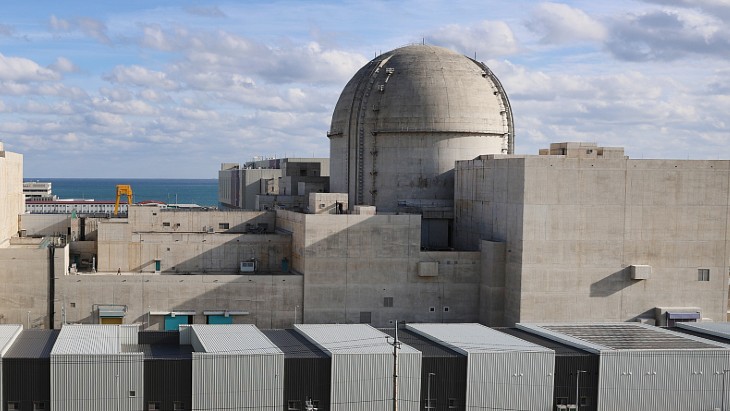

India has been almost completely excluded from international nuclear trade since it refused to sign the 1968 Nuclear non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), calling it unfair. As a result, India developed its own nuclear power program based on pressurized heavy water reactors developed from two Canadian units which began construction in 1964. In addition India has been able to import two pressurized water reactors from Russia, but that deal was unusual having been negotiated outside the NSG.

India has also developed an advanced nuclear fuel cycle concept based on the use of its extensive reserves of thorium in fast breeder reactors, motivated mainly by its exclusion from the international uranium market.

The conditions of the deal stipulate that in order for American companies to supply nuclear reactors, fuel, and fuel-cycle equipment India must, among other things:

- Clearly separate its nuclear industry into civilian and military sectors. US exports will only be permitted for civilian nuclear power use. India published its Separation Plan in March.

- Foreswear nuclear weapons testing forever. The US President must terminate the cooperation agreement if India conducts any nuclear weapons test.

- Increase security at its nuclear weapons facilities.

- Work with the USA to develop a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty to limit the amount of weapons-usable material.

- Allow inspectors from the IAEA into civilian sites, signing the NPT's Additional Protocol which allows more intrusive inspections.

There are critics of the deal in the USA, India and among non-proliferation experts. One observation is that the deal does not limit the production of weapons-usable material or the number of nuclear weapons that India may possess, while India's Bharatiya Janata Party is disappointed that the deal does not assure India a supply of nuclear fuel and does not permit recycling.

Further information

WNA's Nuclear Power in India information paper

WNA's US Nuclear Power Industry information paper

WNA's Safeguards To Prevent Nuclear Proliferation information paper

| INSIGHT BRIEFING What is the Nuclear non-Proliferation Treaty? The main objectives of the NPT are to stop the further spread of nuclear weapons, to provide security for non-nuclear weapon states which have given up the nuclear option, to encourage international co-operation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to pursue negotiations in good faith towards nuclear disarmament leading to the eventual elimination of nuclear weapons. Negotiations on the NPT concluded in 1968 and it came into force in 1970. To date 187 states are party to the NPT, leaving just four outside: Parties to the NPT agree to accept technical safeguards measures applied by the International Atomic Energy Agency. These require that operators of nuclear facilities maintain and declare detailed accounting records of all movements and transactions involving nuclear material. The aim of traditional IAEA full-scope safeguards is to deter the diversion of nuclear material from peaceful use by maximising the risk of early detection. At a broader level they provide assurance to the international community that countries are honouring their treaty commitments to use nuclear materials and facilities exclusively for peaceful purposes. In this way, safeguards are a service both to the international community and to individual states, who recognise that it is in their own interest to demonstrate compliance with these commitments. An Additional Protocol has subsequently been added to the NPT that allows IAEA inspectors more information, greater rights of access and the ability to conduct inspections on just two hours' notice. As of mid-2006, 76 countries plus Taiwan had Additional Protocols in force, 38 more had them approved and signed. Why does India consider the NPT unfair? The NPT essentially draws a 'line in the sand' of nuclear weapons development and places states into one of two categories: NuclearWeapons States, which announced their possession of nuclear weapons before 1970; and non-Nuclear Weapons States which includes every other country. NPT Nuclear Weapons States are: China, France, Russia, the UK and the USA. India had been in the process of developing nuclear weapons while the NPT was under negotiation and exploded its first device in 1974. India was left with the choice of remaining outside the NPT or relinquishing the possibility of maintaining a minimal nuclear deterrent. In the light of perceived strategic challenges from both China and Pakistan, India chose to keep its nuclear deterrent and forego signing the NPT. Only four countries are outside the NPT and all are known to have or suspected of having nuclear weapons. These are: India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan. The NPT itself requires only that internationally-traded nuclear material and technology be safeguarded - a condition that India always made clear it was willing to accept, even though it declines to disarm and join the NPT. In 1992, in an effort to induce expanded participation in the NPT, an informal 'club' of nations called the Nuclear Suppliers Group decided - as a matter of policy, not law - to prohibit all nuclear commerce with nations that have not agreed to full-scope safeguards. This precondition effectively requires countries to join the NPT as non-weapon-states if they are to participate in nuclear commerce. This left India as a pariah in the world of nuclear commerce and India responded by intensifying its embrace of the ethos of self-reliance, maintaining a small nuclear deterrent while pursuing peaceful nuclear power on a ever-larger scale. Why change the rules for India? India has existed outside the NPT for the treaty's entire duration. In that time it has built a strong civilian nuclear sector while maintaining excellent non-proliferation credentials. There has never been any evidence that India has passed on weapons technology, knowledge or skills to any other nation, and the country has lived up to the ambition of the NPT - not to spread of nuclear weaponry while allowing nuclear power to benefit man. The only part of the NPT's vision that India has not taken part in is that of full peaceful cooperation between countries developing nuclear power for their people. India is a rapidly developing country which recognises the need for reliable low-carbon power generation. In coming decades India's contribution to climate change through its carbon emissions is nevertheless set to soar, and so impediments to nuclear development could be seen as an opportunity loss in battling climate change. India is a huge market for the power industry and is very keen to develop its domestic ability quickly. This represents a huge opportunity in a global market which has been neglected for many years and there is certainly very great interest from nuclear suppliers around the world in the possibility of doing business in India. It also follows that India could export its own technology and expertise to other countries. In March 2006 Mohamed ElBaradei, director general of the IAEA said: "This agreement is an important step towards satisfying India's growing need for energy, including nuclear technology and fuel, as an engine for development. It would also bring India closer as an important partner in the non-proliferation regime," said Dr. ElBaradei. "It would be a milestone, timely for ongoing efforts to consolidate the non-proliferation regime, combat nuclear terrorism and strengthen nuclear safety." "The agreement would assure India of reliable access to nuclear technology and nuclear fuel. It would also be a step forward towards universalization of the international safeguards regime. This agreement would serve the interests of both India and the international community." |

_72306.jpg)

_49562.jpg)