World Nuclear Association - and the Uranium Institute before it - has published a report on nuclear fuel supply and demand roughly every two years since its foundation in 1975. The latest report, titled World Nuclear Fuel Report: Global Scenarios for Demand and Supply Availability 2025-2040, was launched in London during World Nuclear Symposium 50, and includes scenarios covering a range of possibilities for nuclear power to 2040.

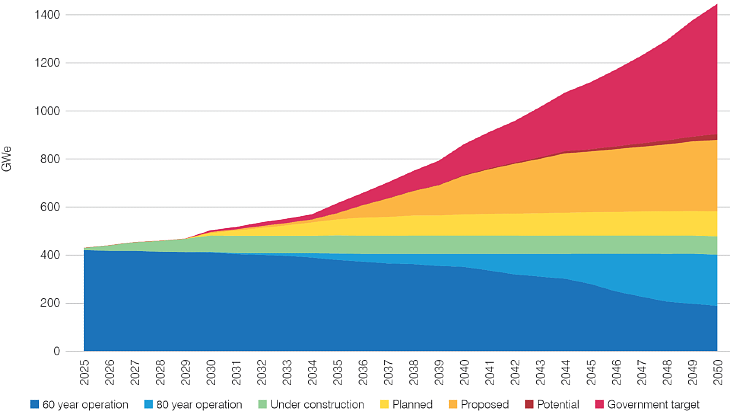

At the end of June this year - the cut-off date for data used in the supply-demand scenarios - world operable nuclear capacity was 398 GWe from 439 units, with 69 units - totalling 71 GWe - under construction. This is projected to increase under all three of the report's scenarios: under the Reference Scenario, which is largely informed by government and utility official targets or objectives, total nuclear capacity is projected to rise to 449 GWe by 2030 and 746 GWe by 2040 (including 49 GWe of capacity from small modular reactors, SMRs). The 2040 figure is some 60 GWe higher than the similar projection in the 2023 edition of the report.

Significant growth is expected in China and India, which together account for more than half of the projected new reactors. Extensions in the operating lifetimes of reactors around the world is also a contributor to capacity growth. Another main reason for the increase in projections is the increased capacity from SMRs.

Most of the demand for uranium for reactors is currently met from so-called primary supply - uranium that is newly mined and processed, and this continues to supply the majority of the demand for nuclear reactors around the globe, the report notes.

Top producing mines are expected to be depleted in the 2030s, which means investment decisions need to be made now, the report says. While the world has plenty of uranium resources, getting it out of the ground in time to meet the growing demand is not so straightforward, as ConverDyn President and CEO Malcolm Critchley, who co-chaired the working group responsible for drafting the report, told World Nuclear Symposium.

"Despite the urgent need for new capacity to be brought online, what we're experiencing is that the time to develop new mines is actually getting longer, not shorter. So in this report, we've changed the expected development timeline from 8 to 15 years to between 10 to 20 years," he said.

"But you can see that we need new supply just to pretty much stay where we are, let alone to meet the growth in demand," Critchley said. "And there's a significant gap between what we call identified sources of supply and sources that are yet to be announced or identified with any sort of level of confidence."

There are significant recoverable resources available to meet even the high scenario, but there is a "tremendous amount of work to be done to bring those identified resources into actual production".

Secondary supplies

Expected primary uranium production alone will not be sufficient to meet demand over the report period. Even under the Reference Scenario, primary uranium supply does not meet demand in the near term, with small quantities of secondary supply bridging the gap. This brings into play other aspects of the front-end of the fuel cycle, including conversion and enrichment supplies.

Secondary sources of uranium supply - from inventories and recycled used fuel, including uranium and plutonium returned back to the fuel cycle after reprocessing - have played a role in bridging the gap between supply and demand, but as the available quantities of such material is decreasing, secondary supplies are seen playing a smaller role in bridging the gap between supply and demand compared with the 2023 edition.

Uranium conversion services are expected to be very tight in the near-to mid-term, raising the risk of supply disruptions, and Critchley said there is a need for significant investment in conversion - "but you can build a conversion plant a lot quicker than a reactor. Once reactor programmes gather momentum, conversion will quickly follow, so there's still time to react".

When it comes to uranium enrichment, on a global scale supply exceeds demand through to at least the early 2030s. Regionally, the picture is more nuanced, with segmentation due to geopolitics as some countries seek to diversify their enrichment supplies to address the market shifts following the Russia-Ukraine conflict. But "given the modular nature of centrifuge technology and the construction times for nuclear power reactors, the expansion of enrichment capacity can take place in a timely way, and supply disruption should be avoided", the report notes.

The fuel fabrication market differs from the other stages of the nuclear fuel cycle due to the specificity of the product: fuel assemblies are highly engineered products, specific to a given reactor technology, and the market itself is more regional in character than global. The report analyses the global fuel fabrication market both by region and by reactor technology, projecting steady increases in fuel fabrication demand in all scenarios from 2027 especially in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. Existing fabrication capacities are sufficient to cover this, but looking ahead, rising demand, especially for new reactor types, will require technological investment, capacity expansion, and market adaptation.

Fuel cycle players are already beginning to respond to the challenges, but more action will be needed to meet demand in the years ahead, Critchley said.

"We have already seen the supply response across all sectors really, but so far it's not been enough to satisfy the projected demand. We can no longer rely on secondary supplies to fill the gap, and the frictionless [global] trade that we had become accustomed to for so long is now experiencing significant challenges."

The Fuel Report Working Group was co-chaired by Cecile Gregoire-David Head of Uranium, Conversion and Enrichment Services at EDF. More information about the report, which is available from World Nuclear Association, can be found here.

_87695.jpg)

_10275.jpg)

_19544_40999.jpg)