Loyiso Tyabashe, CEO of South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (Necsa), outlined the nuclear energy expansion plans in the country and said that its existing reactors mean that South Africa has developed lots of nuclear skills over the years. "But because there have been no new programmes come through, most of our skills have been going to different parts of the world. We had about 200 people who were helping with building their plants in Abu Dhabi. We had some people in the UK at the Hinkley project and the Sizewell project. So we have skills that are overflowing, and we're hoping that as we start our programmes, we'll get those skills back and more other international skills coming back".

Jan van der Lee, Executive Director of France's International Institute for Nuclear Energy (I2EN), which supports education and training in the development of nuclear energy worldwide. explained that "we are in the business of human capacity building on an international level. So what we try to do is to develop the capacity, specifically for countries wanting to develop a nuclear programme. And we do so by looking at the experience we have in France. So in terms of education and training at the academic level, but also a more professional level".

He outlined the French plans for new nuclear capacity - six new EPR2s with more likely to follow - and said that it has been estimated that 100,000 skilled engineers will be needed in the coming ten years. Referring back to the 1970s and 1980s when France built 56 reactors in 20 years, he noted the public confidence in big infrastructure projects and said it was a cause of national pride and a "vision shared by the whole country ... perhaps that's a takeaway for countries wanting to develop a new programme today, is that having more than just an energy policy, but truly a vision for the country where people can be proud, is really extremely helpful in building confidence. And that led to education and training that led to schools and parents being proud, sending their kids to these kinds of engineering schools because they saw the future, this vision, long term."

Martin Darelius, Commercial Manager for New Nuclear and Acting Deputy Head for New Nuclear at Vattenfall in Sweden, said the country was aiming for 2.5 GW of new capacity by 2035 and an additional 10 GW by 2045. He said that, as with France, there had been enthusiasm and training for nuclear skills, but the 1980 decision to shut down nuclear power plants by 2010 was a "wet blanket for all education and nuclear training programmes".

"So we need to really recruit people ... the big challenge that we have is not nuclear science and the nuclear physicists, it's more on the construction workers. The big reason for that is that most of our knowledge and expertise went abroad, just like in South Africa. And the good thing is that they have been within different types of consultant firms and they are now ready to come back and support us in our programme. So that type of knowledge we have. A bigger thing we see as a challenge for our nuclear programme right now is actually people, like we say, who do things with their hands. It's the concrete workers, it's the welders, it's the electricians that are going to install all the equipment. That is not something that has been done on a big scale in Sweden for many years," he said.

Session host Sama Bilbao y León, Director General of World Nuclear Association, agreed with that point: "We are going to need lots of people, this is clear. But not all those people are going to need to be nuclear scientists or nuclear engineers or master's or PhDs. Some, yes, but not that many. We are going to need all kinds of engineers, mechanical or electrical or civil, whatever ... but we are also going to need the welders and the project managers ... and what I would say is this is not a problem that is unique to nuclear energy, or even to energy."

Asked what action needs to be taken to tackle the issue, Tyabashe said the three pillars were firstly, political will and government support, secondly a clear programmatic approach with "with a clear pipeline of skills and other enabling infrastructure", and thirdly, public acceptance: "people do not want to go into an industry that does not seem to be good for humanity" so the nuclear sector has an advocacy role to ensure young people see a job in nuclear as doing good for humanity. Skills will follow if those three conditions are achieved, he said.

Van der Lee agreed with the three points but said public acceptance was the core one, without which there would not be the political will to establish new-build and infrastructure programmes.

Darelius said: "We must look at ourselves as an industry and make our industry attractive for young people to join, and explain why they should work in our industry compared to working with AI and tech companies, which for some people might seem sexier or more well paid or whatever.

"We have had a lot of discussions in the local communities where we are now looking into building new reactors, and explained to them that we come in with jobs that will not be replaced by AI. People will actually work in the plant and it will be very hard for them to be replaced. These are jobs that can be there for a very long time."

Bilbao y León said that over the past decades "many of us in the industry have had a little bit of a defensive stance, we have had a very hard time to be invited to be seated at the table, and we have to had to justify our existence almost every day and I truly believe that the careers of many of the young people that are starting now, or for the emerging leaders of our industry, it's not going to be like that". So, "they are going to face challenges that are quite different from the challenges that we have faced" and she asked, "are we developing them to be protective" when they are accepted and recognised for the delivery of 24/7 clean, affordable electrcity?

Darelius said there was cultural change taking place, with the drive for new nuclear at pace, but this must not be at the cost of safety. Tyabashe agreed on the need for a change of mindset but pointed to the aviation sector for examples of standardisation of design that could speed up construction in different countries: "If you can do it faster and attract the right talent, we need to standardise as much as we can. We know that the youth of today is more mobile than we ever were. And that standardisation is going to encourage that mobility," he said.

Asked about the prospects for bringing people into the nuclear sector from other industries, van der Lee said that France and Canada had been discussing the issue. He said they were looking at creating "bridging training courses in order, for example, to get people from the car industry, mechanical engineers in the car industry" into nuclear but "it's not just a simple walk in the park" and may involve part-time online masters-equivalent courses having to be done around their current jobs.

But he added that there was a lot of innovation in the sector with new SMR and advanced reactor designs, nuclear fusion developments and also opportunities for AI experts in many areas, for example with digital twins and machine learning, and this all made it an attractive career choice.

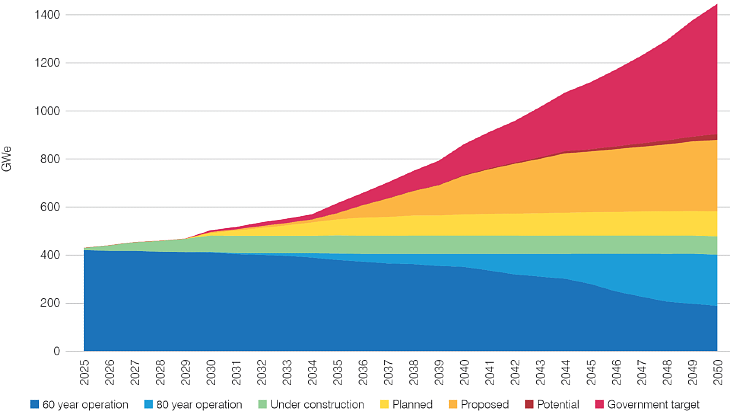

Bilbao y León concluded by asking the panellists how success by 2030 would look. Tyabashe said "we need to be able to see a workforce that can support the at least tripling of nuclear power by 2050. The only way we can do that by 2050 is that by 2030, we have that foundational aspect of having tripled the workforce for construction, because we know that you need many more people to construct these power plants, as well as having ... a skills pipeline for developing and training people to operate those plants".

Van der Lee said "one measure of success would be if we can really increase diversity, because it is something really measurable ... diversity also in terms of internationality ... also in terms of regulation and transparency regulation. I think these are really measurable ways to move forward".

Darelius said success for him would be when nuclear looks like "a very natural part of the educational system". The example he gave was for an option within an electrical engineer's course which included nuclear science "so that becomes something that is very visible for all engineers". He added, that on a broader point, his friends were always surprised to hear about the international collaboration in the nuclear sector. "When I tell them I can pick up the phone and call a nuclear power plant in the US or in France or wherever, because I have a problem, I want help to solve it. And they just raise their eyebrows and wonder why? Why are they giving away all the know-how? Because that is how we do it. And they are people working for Volvo or for some other great Swedish companies, and they can't, they won't be able to call Tesla if they have a problem with the engines or whatever. But in the nuclear industry we do it like this. And the ability to have this international exchange is attractive for young people, especially when going to university. And we should use this more."

Bilbao y León, concluding the session, said there was an enormous opportunity and the key, as Darelius had said, was collaboration. "I'm an international collaborator ... because not one country, not one company, not one continent, not one technology is going to achieve this goal. We really, really, really need to work together."

_19544_40999.jpg)

_66668.jpg)